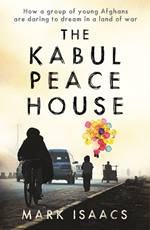

The Kabul Peace House

Mark Isaacs on Radical Thinking

10 Jun 2019 | Cherry Cai

The Mountains, 2008

Insaan stood before a class of university students and delivered his final address.

‘Einstein said when talking about war, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if mankind is to survive.” War is the same old, tragic story. It will never be that new manner of thinking required for our survival, for our freedom from fear and our search for meaning.’1

Insaan had been living in the mountains of central Afghanistan for more than three years, and he resolved that something needed to be done about the disease of warfare. He had approached the local university with an idea to run a peace workshop. He didn’t have a grand plan behind the workshop; he just wanted to start the conversation. The university approved the idea and fifty undergraduates at the university agreed to meet on a weekly basis over a three-month period to discuss whether it was possible to build peace in Afghanistan. Today was the last class of the workshop and Insaan wanted to pose a final question to the students.

‘Martin Luther King spoke of a revolution of values, which will lay hands on the world order and say of war: “This way of settling differences is not just.” Attend to the means by which peace is pursued, Gandhi said, and the ends will look after themselves. There is a blueprint here for a path to peace. Do you think peace is possible in Afghanistan?’2

The culmination of the workshop was that the majority of participants felt peace was impossible in Afghanistan. Insaan understood why the students reached such a conclusion: their experiences over the past few decades left little hope for reconciliation. But he was also slightly stunned by the response. Throughout the workshop, Insaan had tried to open doors in the students’ minds; he had tried to guide them towards different ways of thinking; he had introduced them to different thinkers and activists; all tactics to drive them towards alternatives to warfare, towards methods of peace. The students’ conclusion left the group with the dilemma of endless war. How were they supposed to continue to live with war and this impossibility of peace? Insaan couldn’t accept that. He had to do something. By that time, it had become clear to Insaan that one contributing factor to conflict in Afghanistan was ethnic division. Perhaps it was time Afghans addressed this.

‘Thank you very much,’ Insaan said. ‘It’s been a valuable three months for me. I respect the conclusion of the majority that peace is impossible in Afghanistan. But what are we going to do about this impossibility?’

Insaan looked out across a silent audience who stared back at him, half-fearful, half-expectant. What could they do about an impossibility? They sat on the edge of their seats, holding their breath, waiting for him to offer some ideas.

‘Martin Luther King grew up in a segregated society, where black people drank from different water fountains to white people. Is this what you want for Afghan society? Separate toilets for Hazaras and Tajiks and Pashtuns? There is no segregation by law in Afghanistan as there was in the United States when Martin Luther King was alive, but there is segregation in the workplace. There is social segregation. There is mental segregation. Perhaps segregation begins primarily in the mind. Perhaps that is where we can begin. Would any of you consider living together in a multi-ethnic community for one semester? Think of it as an experiment in peace, an attempt to mend the ethnic disharmony that prevents Afghans from seeing each other as human. If we can create a microcosm of a peaceful multi-ethnic community here in this town, perhaps we can act as an example to the rest of Afghanistan. Perhaps we can be the leaders in a more peaceful future.’

Afghanistan used to be a country connected by interrelated networks of tribes, clans and families. Within these communities, people built and strengthened social networks. That cohesion had been damaged by decades of fighting; Insaan theorised that in order to achieve peace and restore society, Afghans needed to regain that sense of community.

It was a radical idea, a dangerous experiment in a country as divided as Afghanistan. Participants had many people to fear: the religious elite, warlords, the Taliban, their government, their own communities and their own families. And yet, at the end of the class that day, Insaan was surprised to be approached by sixteen male students, from seven different ethnic groups, who wanted to participate in the project. They agreed to live together in one house for one semester.

The first multi-ethnic live-in community consisted of a mixture of Pashtuns, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Tajiks, Sayyids and Pashai. The students moved into a building of four rooms. Insaan chose not to live with the group but instead urged them to make their own observations and draw their own conclusions from the experience, which they communicated to him. Not one member of the group had ever lived with another ethnic group before, let alone six others. This was an opportunity for them to talk about the different ways they ate, prayed and thought. There were personality clashes as expected, but they told Insaan they found the experience to be a positive one overall.

Before starting the project all the students signed an agreement to say that they were willing participants. Many of the students were concerned that the local people and religious leaders would misunderstand the purpose of the exercise, but in the end they decided they were willing to take the risk. It turned out the students’ concerns were not unfounded. They were denied permission to rent a home after telling the owners about the project. In rural towns like the one they lived in, the mosques were intimately involved in the social and political affairs of the area. With that in mind, a few of the students approached the mullah of the local mosque to inform him of the project. Although the mullah never said he was against the idea, it was clear he felt uneasy about mixed ethnic groups of Sunni and Shia Muslims sharing an apartment.

Even though the exercise was run by the university, the local community began to question the students’ involvement in the experiment. Through his work as a doctor in the local area, Insaan had established enough trust in the community to enable him to initiate the university workshop. But the live-in community had the potential to damage his reputation. The local community couldn’t understand why the students would stay together like this in one house and they questioned the purpose of the project. The students were worried about upsetting the very delicate balance of peace in the area.

Despite these fears, the positive experience of the experiment made such an impact on the students that it gave them the courage to carry on with their peace work after the live-in trial ended.

‘The International Day of Peace is coming and we want to celebrate it,’ the students told Insaan.

Insaan had already begun thinking that this group of young people could hold the key to the dilemma of war. If he could recruit young people to this group, a group that conversed with fellow Afghans, discussed basic principles of peace, morality and law, they could build a community that would work together for a better Afghanistan. They would need to place the universal values of peace in the public consciousness, and to do that they would need to take action.

Insaan encouraged the group to involve other young people in the area: their friends, their family members, other students from the university; whoever they could muster. While Insaan wanted this movement to be theirs, he treated their budding sense of social justice like a careful gardener, prompting them with encouragement and suggestions. He connected them with other youth organisations and the local youth directorate of the province.

The community and Insaan went from village to village, visiting the local youth councils. They talked about their wish for peace and they asked young people to register their displeasure against war. Initially not many people responded to their call to action. Insaan put that down to a mistrust of the concept of volunteerism. But through the visits, and other circles and contacts, Insaan and the new activists slowly broadened their sphere of influence. The group of sixteen organised a seminar at the university for the International Day of Peace and they invited the contacts they had made. The young people wore uniformed traditional Afghan dress and addressed the seminar with a short testimony about peace. They then sang the national anthem, with its inclusive line, ‘This is the country of every tribe’, to deliver their message of ethnic unity.

The director of the youth directorate was impressed by the ambitions of the youth and he was in support of the live-in community experiment. He offered his assistance in recruiting more young people and expanding the movement.

At this point the community and Insaan began to start their own local projects. The group’s first demonstration was an international peace trek, in which 150 Afghans walked for peace. They were joined by more than thirty-five internationals from various countries, including staff from more than twenty embassies. They trekked for peace amidst the Hindu Kush mountain ranges, finishing at a pristine alpine lake, 4200 metres above sea level. The youth delivered a speech before their countrymen and the guests, a dignified call for harmony.

Through Insaan’s work in primary health care, he had been exploring a range of ways to help improve living standards in the district and he encouraged the youth to become involved in the local environment movement. They arranged the district’s first ‘clean and green’ campaign to clean up the local township. This campaign paved the way for their first major development project in the area, the building of a peace park.

The Kabul Peace House by Mark Isaacs is AVAILABLE NOW at your local bookstore and online.

Click here to find your local stockist.