Why Berlin City is the most interesting European City

29 Jan 2020 | Julian Tompkin

According to the locals, Berlin is a city that never is but is always becoming. Indeed, with its heady elixir of history, culture and indulgence, the German capital is constantly reinventing itself, making it a curious destination for travellers over the centuries. Julian Tompkin helps you navigate the city in Wanderlust in Berlin taking you to the very best places in its patchwork of uniquely independent boroughs. Take a sneak peek below.

About Berlin

Berlin’s multifarious personality is what makes it wholly unique: a city ripe with contradictions, which is at once ancient yet contemporary, scruffy yet arcadian, traditional yet radical, formal yet irreverent.

Once the capital of the Prussian empire, once a ruin after its nefarious turn with Nazism, once a city divided by the Cold War, today Berlin has faced up to its past and is again a model of tolerance and refuge: a bastion of multiculturalism, progressive political thought and social justice. It’s a city of a little more than 3.5 million inhabitants, reverberating in creativity, character and vitality.

History can be quite the chameleon. Browse its annals prior to the late Middle Ages and Berlin – then little more than a muddy village in Europe’s northern frontier land – barely rates a drop of ink. What we now know as Berlin is in fact the inheritance of two small Slavic villages, Berlin and Cölln – both precariously clinging to a tiny archipelago in the River Spree. It now encompasses the borough of Mitte, featuring the Nikolaiviertel (see p.83), Museum Island (see p.69) and the Fischerinsel (what remains of the ancient settlement of Cölln, see p.69). The outlying Brandenburg villages of Spandau and Köpenick – now integral parts of Berlin – first appear in historical documents around the same time, all dating back to the 12th century.

The area was the fractious fiefdom of local warlords (including Slavs, Bohemians and Teutons), amongst them Jaxa of Köpenick: the final Slavic ruler before the Germanic Albert the Bear wrestled control in the 12th century, thus proclaiming it the Margraviate of Brandenburg principality. The Slavic Wends (known locally as Sorbs) gifted Berlin its name: Brlo, which loosely translates to ‘habitable place in marshland’ – and Jaxa’s Sorbian inheritors remain in the region to this day, most notably in the Spreewald region south of Berlin, famed for its sublime gherkins and network of idyllic waterways.

Berlin remained relatively inconspicuous – a backwater, traded amongst the European gentry and Teutonic Knights – until 1410, when Roman Emperor Sigismund gifted the Margraviate to an ambitious dynasty from southern Germany, the Hohenzollerns, which ruled until the end of World War I. In 1415, Friedrich IV of Nuremberg became Friedrich I of Brandenburg, and within two centuries the region had – through intermarriage with Baltic nobles – metamorphosed into the Kingdom of Prussia: one of world history’s leading players.

This pristine and wild expanse of forest and lakes suddenly found itself embroidered with resplendent palaces and manors. The bridle trail between Potsdam and Berlin was renamed Schlossstrasse (Palace Road), linking the regal nerve centres of this quickly expanding empire that would, at its zenith in the 18th and 19th centuries, reach from Belgium to Lithuania. Under 18th-century ruler Friedrich the Great, Prussia evolved into one of the world’s most formidable – and feared – militarised states, earning the Prussians a reputation for being both cunning and imperialistic: contradicted by Friedrich’s deep love of art, and his quest to make Berlin a global epicentre of the Enlightenment.

Throughout the centuries, Berlin had a reputation as a city of tolerance and refuge: opening its fortified city gates to the persecuted and exiled, including French Huguenots, Protestant Bohemians and Moravians and Jewish peoples expelled from Russia’s Pale of Settlement.

Prussia became the mightiest power in Europe following victories against Austria and France in 1871, and Berlin soon found itself the capital of a newly unified Germany – with Wilhelm I crowned its head as German Emperor. His eventual successor Wilhelm II, however, would steer Prussia and its capital towards wreck and ruin. Germany ended World War I in total defeat, with the abdication of Wilhelm II and the end of the Hohenzollern dynasty, the dismantling of the Prussian state and the 1919 Treaty of Versailles reparations that would cripple the optimism of the Weimar Republic (1918–33) … and arguably portend the rise of Nazism.

Nazi atrocities would be avenged with the near erasure of the city centre, with scant little remaining to speak of its ancient history beyond charred and skeletal ruins. Today there are few survivors: amongst them the Totendanz (Dance of Death) frieze in the Marienkirche (St Mary’s Church, see p.83) an ancient and auspicious prophecy of this city’s often all-too fatalistic flirtations with doom.

Post-World War II, the Cold War saw Berlin quartered by the Allies: dividing kin and fellow Berlin citizens behind the concrete Berlin Wall for nearly 30 years and creating a city with two distinct and often incongruous personalities. East Berlin gazed east beyond the Vistula River to Russia, and West Berlin gazed west beyond the Rhine. The ‘Wende’ – or peaceful revolution – in the East would triumph on 9 November 1989 when the Wall finally fell. But despite reunification in 1990, Berlin today remains a mosaic of its enigmatic history: the East and the West still evident in the most humdrum of manifestations, including the East’s‘ Ampelmann’ pedestrian light symbols – a somewhat kitsch red and green figure of a man in a hat that’s transformed from a curiosity into a cultural icon – from its communist past.

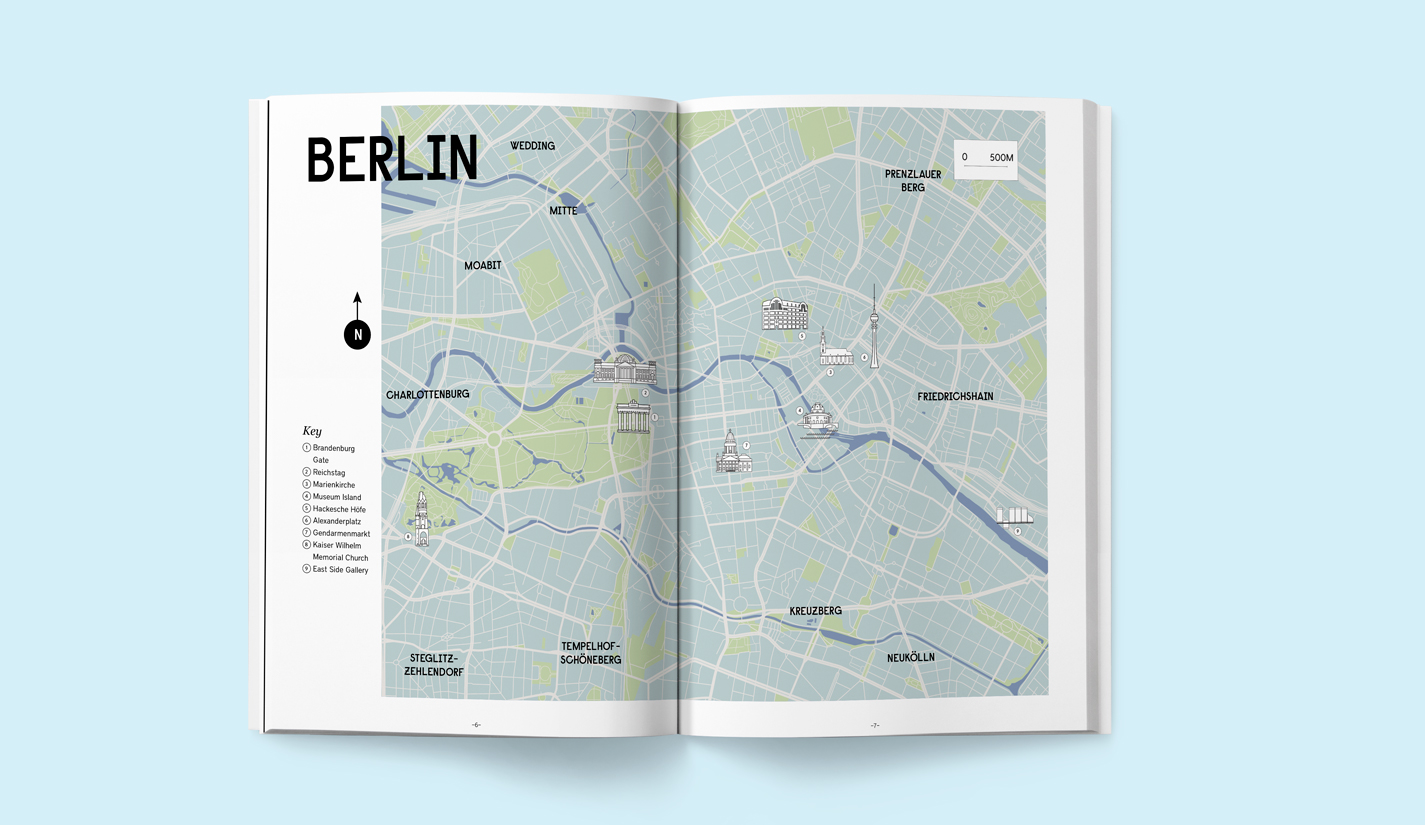

Three decades on from reunification, satellite imagery still reveals the demarcation scars between the East and the West: the East warm with bronze gaslight, the West in fluorescent white. In a city with distinct kieze (neighbourhoods) and an eclectic personality, orientation is in the eye of the beholder. The River Spree cuts roughly east–west across the city and the Havel river runs north–south on the city’s western fringe. The borough of Mitte (meaning middle) sits at its geographic heart, surrounded by key inner-city boroughs, including Prenzlauer Berg, Kreuzberg, Friedrichshain and Neukölln.

While populous, the city carries a relaxed air, never feels too crowded and is fabled for its clean air and abundance of lakes and green spaces. It has a fantastic public transport network of trains, trams and buses but is also notoriously flat – so it's perfect (and safe) for cycling.

Today Berlin finds itself at the epicentre of European power once more: politically and economically. Yet its affordable rents (a legacy from East German socialism, where apartments were state owned) and enduring aura of ramshackle chic have maintained its vibrancy. It's a city where history is conspicuous: where detailed information panels never shy away from the truth and brass pavement plaques called Stolpersteine (tripping stones) mark where Jewish victims of National Socialism once lived.

It’s difficult to graft a Berliner: they’re a people notorious for their resilience as much as their no-nonsense demeanour. Echte Berliners (real Berliners) are often characterised by their proud gruffness – what other Germans identify as the ‘Berliner Schnauze’ (Berliner snout): a demeanour and vernacular that is proudly unvarnished and bluntly forthright.

Gastronomy here is both avant-garde and folkish. A rich mosaic of regions, ‘German cuisine’ is an olio of distinct regional styles and ‘Berliner Küche’ (kitchen) is itself a historical pastiche, befitting its once-imperial reach and historical centre as a city of ravage, ruin and refuge.

Berlin is also a city where life is visceral. Where museums are world-renowned and art galleries cast out far beyond the cutting-edge. It has long been a magnet for artists: with around 20,000 living and working in the city today, drawn by its edginess and cheap rents. In 2005 UNESCO ordained Berlin a City of Design, and today it’s home to over 700 official art galleries and a vibrant street art scene. Also boasting four world-class theatre companies, three globally renowned opera companies and the courted Philharmonic Orchestra, Berlin has been re-branded the ‘The City of Art’.

Which will be your Berlin?

Michelberger Café & Bar

One of the city’s trendiest addresses, in which to both work and play.

The Michelberger Hotel shifted the urban landscape in Berlin and also the once

run-down borough of Friedrichshain: now effortlessly hip with a pinch of style and luxury that was once anathema to this part of Friedrichshain. Today the hotel is the go-to destination for rockers and fashion doyens passing through, and its lobby bar has become a beacon for Berlin’s transient laptop warriors and after-work revellers, keen to soak up its mash-up aesthetic between playful and austere and enjoy an espresso or Michelberger Sour.

With its sun-laden courtyard, the Michelberger is an urban idyll from where you can while away an afternoon in the company of Berlin’s modish denizens. And while you people-watch, you can drink a beer from cult Danish brewery Mikkeller: a pilsner made exclusively for the bar.

|

Warschauer Strasse 39–40 |

|

|

|

S + U-Bahn Warschauer Strasse |

29 77 85 90 |

This is an edited extract from Wanderlust in Berlin by Julia Tompkin

Available now in all good bookstores

Click here to find your preferred online retailer